Finite capacity scheduling is how metal fabrication job shops build production schedules that reflect reality: the actual hours in your weld bays, brake, laser, paint booth, and assembly, plus the constraints that decide what can run next.

If you’re scheduling in Excel (or a whiteboard), you’ve seen the pattern: the plan looks solid until the shop floor hits it. A rush job lands. Material is late. A welder is out. Paint is booked. One bottleneck shifts, and suddenly you’re cutting and pasting rows, chasing updates, and making promise dates you can’t trust.

This guide is written for job shops and small-to-mid metal fabricators, not generic manufacturing. You’ll learn what finite capacity scheduling means in job-shop terms, the minimum inputs you need for it to work, and a practical way to plan and replan without your schedule turning into fiction.

What is finite capacity scheduling?

Finite capacity scheduling is a production scheduling method where you load work into your plan only up to the real capacity you actually have: available labor hours, machine hours, shift calendars, and the constraints that limit flow (bottlenecks, setups, material readiness, and shared resources). When demand exceeds capacity, the system pushes operations out in time instead of pretending everything can still ship on the original date.

The opposite is infinite loading (sometimes called infinite capacity scheduling). It’s the default in a lot of spreadsheets and even some ERPs because it’s easy: you drop jobs onto a timeline based on due dates and estimates, without enforcing capacity limits. It “looks fine” until you hit the week where welding is booked at 180%, paint is stacked three jobs deep, and the only way to hit the schedule is overtime, expediting, or slipping deliveries. Infinite loading doesn’t prevent overload, it just hides it until it becomes a fire.

Finite vs infinite scheduling

If you’ve ever felt like your schedule is technically planned but practically unusable, you’re probably running infinite loading. Finite capacity scheduling is the shift from planning by due date to planning by what the shop can truly produce. Let’s take a look at the below comparison table.

| What changes | Finite capacity scheduling | Infinite loading |

|---|---|---|

| Promise dates | Move when capacity is full (more realistic) | Stay optimistic until you miss them |

| Overloads | Visible immediately (where/when you’re over capacity) | Hidden until the floor can’t keep up |

| WIP levels | Lower and more controlled (less “start everything”) | Often higher (jobs sit waiting at bottlenecks) |

| Expediting | Less “hero mode” because conflicts show earlier | More expediting because conflicts show late |

| Replanning effort | Changes are structured (move work, see impact fast) | Changes are manual domino effects (spreadsheet chaos) |

| Shop-floor trust | Higher, because the plan reflects reality | Lower, because the plan is constantly wrong |

Why finite capacity matters in metal fabrication

Finite capacity scheduling matters in every manufacturing environment, but it’s especially important in metal fabrication job shops because your work is rarely repeatable and your constraints are usually shared.

In a high-volume assembly line, the shape of work is predictable. Routing is stable, cycle times are known, and the biggest scheduling problem is often sequence optimization. In a job shop, the problem is more basic and more brutal: you can’t schedule what you can’t physically produce with the people and equipment you have this week.

Here’s why finite capacity scheduling fits metal fabrication better than generic scheduling approaches:

1) You’re running project-based, custom work

In a fabrication shop, every job has its own mix of drawings, weld complexity, tolerances, revisions, and “unknown unknowns.” Even when two jobs look similar on paper, one can run smooth and the other can stall on fit-up, rework, or missing information.

That variability makes “due date schedules” fragile. Finite capacity scheduling forces you to plan with a buffer for reality and makes it obvious when your current load is based on hope or gut feeling instead of capacity.

2) Your bottlenecks are shared and non-negotiable

Most fab shops don’t have unlimited parallel resources. You might have:

- one paint booth (or a single powder coat window)

- a limited number of weld bays

- one press brake operator everyone depends on

- a crane that turns into a hidden constraint

- a laser that becomes the entire week’s pace-setter

Those shared constraints dictate what can move next. Infinite schedules ignore them until the bottleneck is overwhelmed. Finite capacity scheduling puts bottlenecks on the map, so you can see the squeeze early and plan around it instead of discovering it when everything is already late.

3) Disruptions aren’t edge cases, they’re the weekly norm

In metal fabrication, “the schedule changed” isn’t a rare event. It’s normal. Common disruptors include:

- rework and quality issues that eat capacity without warning

- missing drawings or late approvals that block start dates

- late material or incorrect deliveries that stall work-in-progress

- subcontractor lead times (galvanizing, machining, powder coat) that shift unexpectedly

- rush orders that force reprioritization mid-week

A schedule that can’t adapt quickly becomes useless. Finite capacity scheduling gives you a structure for replanning: when something changes, you adjust load against capacity and immediately see what has to move.

4) The real cost shows up as late deliveries and “hero mode”

When you overbook a fab shop, you don’t just miss dates. You pay for it in a bunch of ways that quietly wreck margins:

- late deliveries and customer frustration

- overtime that becomes permanent

- expediting (last-minute purchasing, hot-shot deliveries, priority subcontracting)

- excess WIP that clogs the floor and hides what’s actually urgent

- constant firefighting that burns out your best people and makes planning feel pointless

Finite capacity scheduling is fundamentally a margin protection tool. It helps you stop promising more than you can deliver, keep WIP under control, and make change decisions deliberately instead of emotionally.

If your shop feels like it’s always busy but still late, the issue often isn’t effort. It’s that the schedule isn’t capacity-based. In job-shop fabrication, scheduling “to reality” is the difference between running the business and chasing it.

The constraints you must model to Make your Schedule finite

A lot of shops say they “do finite capacity scheduling” when what they really mean is: we estimate hours and try not to overload the week too badly. That’s a start, but it’s not truly finite unless your schedule respects the constraints that actually decide whether work can move.

You don’t need a perfect model of your shop to get value. But you do need to model the few constraints that create 80% of schedule failure in metal fabrication.

Capacity by department/work center

Start by defining capacity where work actually flows, not where it looks neat on an org chart. For most fab job shops, that’s departmental or work-center capacity like:

- Cutting: laser, plasma, saw (including nesting and prep time)

- Brake/forming: press brake time is often a hidden bottleneck

- Welding/fabrication: weld bays, fit-up, rework capacity

- Grinding/finishing

- Paint/powder coat: often the pace-setter for shipping dates

- Assembly

- Install/field work (if you do it)

The key is simple: each work center has a limited number of hours per day/week. A finite schedule must fill the bucket without exceeding it. If welding is booked, jobs must move. If paint is the bottleneck, paint drives promise dates.

Tip: if you’re starting from scratch, schedule at the department level first (hours per day/week). You can always add operation-level detail later, but most shops get control faster by making the big constraints visible first.

Labor reality (skills + shifts)

This is where a lot of scheduling breaks down. Headcount is not capacity.

10 people does not mean 10 interchangeable units of production time. In a fab shop, capacity depends on:

- who can run the laser vs who can only assist

- who is certified for certain weld procedures

- who can do fit-up without supervision

- who can run the press brake efficiently

- who is on which shift, and who is actually available this week

A finite schedule needs capacity in the form that matters: skilled hours. If your best brake operator is on vacation, your brake capacity isn’t “8 hours/day,” it’s whatever the remaining team can realistically deliver without quality or rework exploding.

Even a simple capacity calendar per department that reflects shifts, planned absences, and major constraints will make your schedule dramatically more honest.

Setup/changeover + batching

If you ignore setup and changeover, your schedule will look efficient on paper and run inefficiently in reality.

Fabrication has lots of invisible time that eats capacity:

- press brake tooling changes

- fixture swaps in welding

- paint booth changeover (colors, cure cycles, cleaning)

- machine setup, programming, and first-article checks

- crane moves and staging time

This is why sequencing matters. Two examples:

- Paint: grouping jobs by color or coating type can prevent the paint booth from becoming a constant stop-start machine.

- Welding: running similar fixturing back-to-back reduces setup time and improves throughput.

Finite capacity means you acknowledge that a “2-hour weld” might not be 2 hours when it’s split across three setups and two interruptions.

A practical approach here would be to add a simple setup allowance per job/phase (or per changeover type) and use batching rules for the biggest offenders (often paint and brake).

Material readiness

This is the most common reason schedules lie.

If the cut list isn’t ready or material isn’t on the floor, the job can’t start, no matter what your Gantt chart says. Scheduling “phantom work” creates false confidence and then triggers panic later.

For a finite schedule to hold, you need a basic readiness gate. Before a job enters the active schedule, confirm:

- drawings released (and revisions under control)

- cut list/BOM available

- critical material ordered and due (or received)

- subcontract steps booked (if needed)

You just need a simple status that makes “not ready” obvious so you don’t plan work that cannot physically begin.

Subcontracting (treat lead time as a constraint)

Most job shops rely on outside processes at some point:

- galvanizing

- powder coating

- machining

- heat treatment

- specialty finishing

Subcontracting is a common scheduling constraint that can dictate your ship date more than your internal capacity.

In a finite schedule, subcontract steps should be treated as:

- a real calendar block (days out of your control)

- with variability (because subcontractor lead times change)

- and a pickup/return buffer (transport, queues, inspection)

If you ignore this, you end up with the classic problem: internal work finishes “on time,” then the job sits waiting on coating, and the customer only hears about the delay when it’s already unavoidable.

Quick checklist: before you schedule a job, do you have…?

| Readiness / constraint check | Why it matters |

|---|---|

| Drawings released + latest revision confirmed | Prevents mid-job changes and rework |

| Defined job phases/routing (cut, brake, weld, paint, assembly, install) | You can’t load capacity without a flow |

| Estimated hours by phase (even rough) | Finite scheduling needs time demand |

| Department/work-center capacity set (hours/day or week) | Otherwise it’s not finite |

| Labor reality accounted for (skills, shifts, absences) | Headcount ≠ capacity |

| Key materials on hand or confirmed due date | Don’t schedule jobs that can’t start |

| Subcontract steps planned (booked + lead time + buffers) | External time often drives ship date |

| Setup/changeover assumptions (at least for major bottlenecks) | Stops “paper efficiency” from lying |

If you model these constraints, your schedule starts behaving like a tool instead of a guess. And when something changes (because it will), you can replan quickly without blowing up the whole week.

Two ways job shops run finite scheduling

When people talk about finite capacity scheduling, they often picture an advanced job shop software that optimizes every routing step down to the minute.

In practice, job shops, who don’t use an advanced scheduling system like EZIIL, run finite scheduling in two common ways. Both can work. The difference is how much detail you model and how much effort it takes to keep the data clean.

Department-level finite scheduling (best for small shops getting control fast)

This is the most practical starting point for most fabrication shops.

You schedule at the department or work-center level using rough-cut capacity: available hours per day or per week. The goal is to stop overbooking your bottlenecks and to create a schedule the shop can actually follow.

What it looks like:

- You break jobs into phases (cut, brake, weld, paint, assembly, install)

- You estimate hours per phase (even if they’re rough)

- You set capacity per department (hours/day or hours/week, adjusted for shifts and absences)

- You load work until capacity is full

- When a department is full, the schedule pushes out and you see it immediately

Why it works so well in job shops:

- It reflects how most fab shops manage work anyway (department flow, not perfect op-by-op routing)

- It’s fast to implement and maintain

- It surfaces the real problem quickly: “We’re overloaded in welding next week” or “paint is booked solid for 10 days”

It’s also the quickest route to two outcomes your customers care about:

- Stop overbooking. You can see overloads before they become late jobs.

- Promise dates that hold. If capacity isn’t there, you don’t pretend it is.

If your schedule currently collapses into daily firefighting, department-level finite scheduling is usually the highest ROI move you can make.

Operation-level Advanced Planning and Scheduling (when you truly need it)

Operation-level APS (Advanced Planning and Scheduling) is the full-detail version: each job is scheduled through its specific routing steps, often with sequencing rules and optimization across machines, setups, and constraints.

It can be powerful when you truly have:

- very complex routings (many operations with dependencies)

- heavy sequencing requirements where setup minimization drives major savings

- many alternative machines/work centers that can run the same operation

- high volume or high mix where minute-level sequencing materially affects throughput

But here’s the tradeoff: APS only works when your data is reliable enough to support it.

APS typically requires:

- accurate routings and standard times per operation

- reliable setup/changeover times

- clean calendars by machine and labor

- real-time shop-floor feedback (or frequent updates) so the plan doesn’t drift

- discipline in how jobs are released and tracked

If those inputs aren’t solid, APS becomes an expensive way to generate a schedule that looks impressive and fails by Tuesday.

That’s why many job shops get better results starting with department-level finite scheduling first. It builds the operating muscle: estimating hours, tracking reality, seeing bottlenecks, replanning fast. Then, if you outgrow it, you can move toward more detailed scheduling with far less pain.

Decision guide: where to start

If you’re a 10-80 person metal fabrication job shop, start with department-level finite scheduling in almost every case.

Start with department-level finite scheduling if:

- your schedule changes daily and you’re constantly expediting

- Excel/whiteboards are still the source of truth

- you don’t have consistent routings and time standards

- your biggest problem is overload visibility and realistic promise dates

- you need something your team will actually maintain

Consider operation-level APS later if:

- you already have clean routings and accurate time data

- sequencing and setups are a major driver of profitability (especially in bottleneck work centers)

- you have enough volume/complexity that minute-level optimization pays off

- you have a strong feedback loop from the floor to keep the plan current

A good rule of thumb: get finite at the department level first, then earn the right to go deeper. In metal fabrication, the “perfect schedule” isn’t the goal. A schedule the shop can trust and adapt quickly is.

How to build a finite capacity schedule in a job shop

This is the section that matters. Finite capacity scheduling requires a repeatable process that turns “what we want to do” into “what we can actually do”, and makes replanning fast when reality changes.

If you run a metal fabrication job shop, here’s a practical way to do it.

Step 1: List active jobs + due dates (and pick a planning horizon)

Start with a single, current list of active jobs that includes:

- job/project name

- customer

- ship date (or required-by date)

- priority (rush, standard, internal)

- current status (not started / in progress / blocked)

Then choose a planning horizon that matches how your shop actually operates:

- 2 weeks if you’re reactive and want quick control

- 4-6 weeks if you’re booking work and promising dates regularly

- 8+ weeks only if your inputs are stable enough to keep it from turning into fiction

Important: your schedule is not your backlog. Your backlog can be months long. Your schedule should reflect the window where you can actively manage flow and capacity.

Tip: If you’re not sure, start with 4 weeks. It’s long enough to see bottlenecks forming and short enough to stay maintainable.

Step 2: Break each job into phases with hour estimates

Job shops don’t need perfect routings to run finite scheduling. They need consistent phases that reflect how work moves through the shop.

A simple default for metal fabrication is:

Prep → Cutting → Welding → Paint → Assembly → Install

Not every job uses every phase. That’s fine. The point is to load the right departments with the right time demand.

For each active job, estimate hours per phase. Keep it practical:

- Use rough ranges if needed (ex: welding 18-24 hours)

- Start with “good enough” estimates and tighten over time

- If you have no baseline, use last jobs as reference (even informally)

Two rules that keep this useful:

- Estimate the bottlenecks first. If you only get welding and paint right, you’ll already be better than most schedules.

- Don’t hide uncertainty. If a job has risk (unknown fit-up, complex welds, unclear drawing), add a buffer to that phase rather than pretending it’s clean.

Step 3: Set your real capacity (include buffers)

Now define capacity in the simplest usable form: available hours per department per day/week.

Example (illustrative):

- Cutting: 40 hours/week (1 machine, single shift, minus planned downtime)

- Brake: 32 hours/week (operator is shared, plus meetings/setup reality)

- Welding: 120 hours/week (3 welders × 40h, adjusted for absences)

- Paint: 30 hours/week (one booth + cure constraints)

- Assembly: 60 hours/week

The mistake is scheduling to theoretical maximum. In job shops, that creates cascading late work because anything unexpected tips you over.

That’s why many planners deliberately schedule to 85-90% of capacity, especially at bottlenecks.

Why it works:

- It creates breathing room for rework, rush jobs, and changeovers

- It reduces the “everything is late at once” scenario

- It makes the schedule more believable to the floor

If you want a simple starting point:

- set capacity at 90% for most departments

- set capacity at 80-85% for your most volatile bottleneck (often welding or paint)

Then adjust based on what actually happens.

Step 4: Load jobs to capacity (and let dates move if capacity is full)

This is the “finite” part.

Load each job phase into the schedule until the department’s available capacity is full. When you hit the limit, you don’t cram it in anyway. You let the work move later.

In plain language, “push out” means:

If welding is fully booked next week, the welding phase of the next job can’t happen next week. So its welding starts the following week, and everything downstream (paint, assembly, ship date) moves accordingly.

This is where infinite schedules lie: they keep everything on the original due date even when the shop is overloaded, and the only way to make the lie true is overtime or missed deliveries.

A finite schedule forces the honest conversation early:

- Do we accept a later ship date?

- Do we add overtime?

- Do we shift resources?

- Do we reprioritize another job?

You’re not “failing” when dates move. You’re seeing reality early enough to act.

Step 5: Pick simple sequencing rules

You don’t need complex assurance algorithms to improve scheduling in a fab shop. Start with simple rules that fit how your constraints behave.

Three rules cover most job shops:

1) Earliest due date (EDD)

- Works well when customer delivery commitments are the main driver

- Watch out: it can overload bottlenecks if you don’t also look at capacity

2) Bottleneck-first

- Prioritize the work center that dictates the whole flow (often welding or paint)

- Schedule bottlenecks first, then feed the rest of the shop around them

- This prevents “everything is started, nothing is finished”

3) Batch-by-setup

- Especially useful for paint and certain welding fixtures

- Group work to reduce changeovers (color changes, fixture swaps, tooling changes)

A practical approach: run bottleneck-first, then sequence within that bottleneck by EDD, with batching rules for the biggest setup drains (paint is a common one).

Step 6: Lock the near term, stay flexible further out

One reason schedules fail is constant churn. If the shop believes the schedule will change every hour, they stop trusting it.

A good job-shop practice is to establish a freeze zone:

- For the next X days, the plan is locked (except true emergencies)

- Beyond that, the schedule can be adjusted as new information comes in

Typical freeze zones:

- 2-3 days for highly reactive shops

- 1 week for more stable environments

This creates a balance:

- The floor gets stability and clarity for near-term execution

- Planning remains flexible enough to handle real-life change

Step 7: Update daily from the floor (the schedule is only as good as the feedback loop)

Finite capacity scheduling is not a one-time plan. It’s a daily loop:

- the shop executes

- reality produces signals (done, delayed, blocked)

- the schedule updates

- you replan based on actual capacity and status

A minimum daily update rhythm looks like:

- What finished yesterday?

- What’s blocked, and why?

- What changed (materials, priorities, downtime)?

- What needs to move so the bottleneck stays productive?

If you don’t update, your schedule becomes stale and you’re back to running off gut feel and verbal updates.

You don’t need perfect time tracking. You need consistent status updates and a habit of reflecting them in the plan.

Mini worked example: one weld bottleneck pushes the final date

Let’s say you have three jobs moving through the shop. Your weekly welding capacity (after buffer) is 90 hours.

Welding hours required:

- Job A: 40 hours (due in 2 weeks)

- Job B: 35 hours (due in 3 weeks)

- Job C: 30 hours (due in 3 weeks)

Total welding demand for next week is 105 hours, but capacity is 90.

In an infinite schedule, all three jobs stay “on track,” and the plan assumes welding will somehow complete 105 hours in 90 hours. What happens in reality is predictable:

- someone gets pulled into expediting

- overtime becomes “required”

- Job C slips quietly until it’s suddenly urgent

In a finite schedule, the result is honest:

- You load Job A (40h) and Job B (35h) = 75h

- You have 15h of weld capacity left

- Job C gets 15h next week and 15h the following week

That “pushes out” Job C’s downstream phases:

- Paint and assembly start later

- The ship date moves unless you add overtime, shift labor, or change priorities

Now you can make a decision while there’s still time:

- Can we pull another welder onto Job C?

- Can we split Job C into phases and start prep/cutting while welding capacity frees up?

- Can we negotiate a realistic delivery date with the customer today instead of apologizing later?

That’s the real value of finite capacity scheduling in a job shop. It turns hidden overload into visible decisions you can act on early, without your entire week turning into chaos.

How EZIIL software solves finite capacity scheduling for steel fabricators

If you’re a small-to-mid metal fabrication job shop, you usually don’t need a perfect APS optimizer. You probably need a system that makes capacity visible, keeps the schedule honest, and lets you replan fast when reality changes.

That’s where EZIIL Starter fits well.

Finite-by-design at the department level

EZIIL’s MasterView is built for planning based on real departmental capacity (hours per day). You set available resources per department, and the plan is calculated against that availability. When a department is overloaded, it shows up immediately in the resource view so you can see the bottleneck before it turns into late deliveries.

In other words: you’re planning against available hours, not hoping the shop can magically do 105 hours of welding in a 90-hour week.

Fast replanning without spreadsheet domino effects

In real job shops, the plan changes constantly. EZIIL supports manual adjustments directly in the schedule (drag-and-drop and date edits) so you can move work without the “cut, paste, recalc, break formulas, repeat” loop.

The goal is, when a rush job lands or paint gets booked, you can adjust the plan quickly and see the impact, instead of rebuilding the week from scratch.

Job phases that match metal fabrication flow

EZIIL is naturally structured around the way fab shops run work through departments and phases. You can break a job into the steps that actually matter to your shop (for example cutting → welding → painting → assembly) and keep work sequenced in a way that makes sense operationally.

This matters because generic tools often force you into either:

- overly detailed routings you can’t maintain, or

- vague task lists that don’t translate into capacity planning

EZIIL sits in the practical middle: detailed enough to plan, simple enough to keep current.

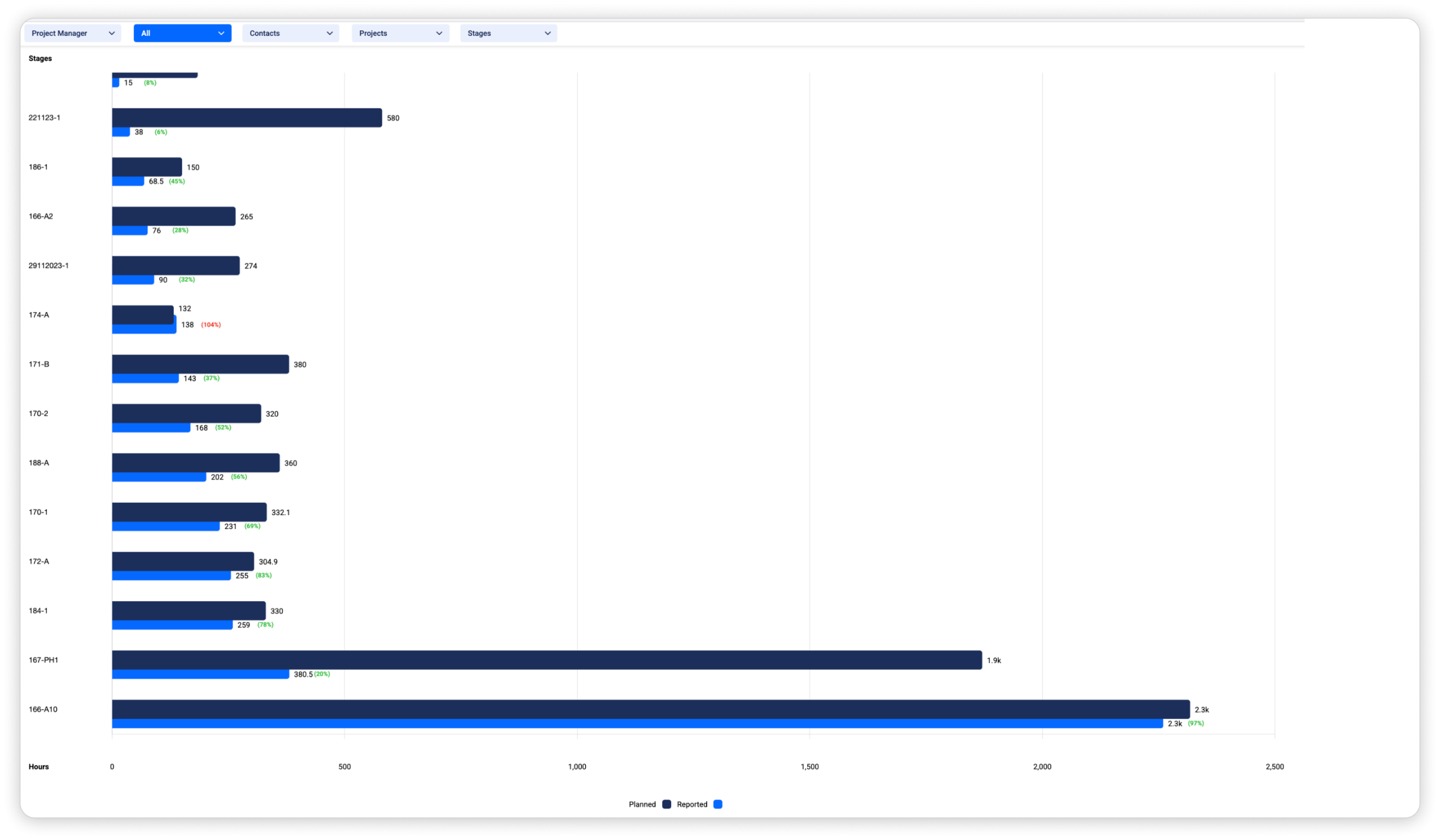

Plan vs reality feedback loop (so estimates improve over time)

Finite scheduling only stays useful if you have a feedback loop from the floor.

EZIIL supports shop-floor reporting (mobile/web), plus manager confirmation of reported time. That gives you:

- real progress updates (what’s running, what’s done, what’s delayed)

- visibility into planned vs actual hours

- better future estimates because you’re not guessing forever

Over time, this is how scheduling and quoting get sharper: your planned hours become grounded in what the shop actually took, not what you hoped it would take.